di·a·be·tes (di

-be´t

-be´t z)

[ Gr. diab

z)

[ Gr. diab t

t s a

syphon, from dia through +bainein to go ]

s a

syphon, from dia through +bainein to go ]

1. any of various disorders characterized by

polyuria. 2.

d. mellitus.

adult-onset diabetes mellitus,

type 2 d.

mellitus.

alloxan diabetes, an animal model for diabetes mellitus;

administration of

alloxan produces selective destruction of the

beta cells of

the pancreas, causing hyperglycemia and ketoacidosis.

brittle diabetes,

type 1 diabetes

mellitus that is characterized by wide, unpredictable fluctuations

of blood glucose values and is difficult to control.

bronze diabetes, bronzed diabetes,

hemochromatosis.

central diabetes insipidus,

diabetes

insipidus due to injury of the neurohypophysial system, with a

deficient quantity of

vasopressin

being released or produced, causing failure of renal tubular

reabsorption of water. It may be inherited, acquired, or idiopathic.

Called also

pituitary d. insipidus.

chemical diabetes, former name for

impaired glucose

tolerance.

gestational diabetes, gestational diabetes mellitus,

diabetes mellitus

with onset or first recognition during pregnancy; it does not include

diabetics who become pregnant or women who become lactosuric.

growth-onset diabetes mellitus,

type 1 d.

mellitus.

diabetes insi´pidus, any of several types of

polyuria in

which the volume of urine exceeds 3 liters per day, causing dehydration

and great thirst, as well as sometimes emaciation and great hunger. The

underlying cause may be hormonal (central

d. insipidus) or renal (nephrogenic

d. insipidus).

insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus,

type 1 d.

mellitus.

juvenile diabetes mellitus, juvenile-onset diabetes mellitus,

type 1 d.

mellitus.

ketosis-prone diabetes mellitus,

type 1 d.

mellitus.

ketosis-resistant diabetes mellitus,

type 2 d.

mellitus.

latent diabetes, former name for

impaired glucose

tolerance.

lipoatrophic diabetes,

total

lipodystrophy.

malnutrition-related diabetes mellitus, a rare type of

diabetes mellitus

associated with chronic malnutrition and characterized by beta-cell

failure, insulinopenia, insulin resistance, and moderate to severe

hyperglycemia, but without ketosis. Called also

tropical or

tropical

pancreatic d. mellitus.

maturity-onset diabetes mellitus,

type 2 d.

mellitus.

maturity-onset diabetes of youth, maturity-onset diabetes of the

young, an autosomal dominant variety of

type 2 diabetes

mellitus, classified into several types on the basis of the mutation

involved, characterized by onset in late adolescence or early adulthood.

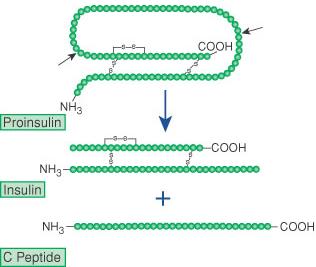

diabetes mel´litus, a chronic syndrome of impaired carbohydrate,

protein, and fat metabolism owing to insufficient secretion of insulin

or to target tissue insulin resistance. It occurs in two major forms:

type 1 d.

mellitus and

type 2 d. mellitus, which differ in etiology, pathology, genetics,

age of onset, and treatment.

nephrogenic diabetes insipidus,

diabetes

insipidus caused by failure of the renal tubules to reabsorb water

in response to

antidiuretic hormone, without disturbance in the renal filtration

and solute excretion rates; characterized by polyuria, extreme thirst,

growth retardation, and developmental delay. The condition does not

respond to exogenous vasopressin. It may be inherited as an X-linked

trait or be acquired as a result of drug therapy or systemic disease.

non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus,

type 2 d.

mellitus.

pituitary diabetes insipidus,

central d.

insipidus.

posttransplant diabetes, glucose intolerance or overt

hypoglycemia that first appears after an organ transplant; some cases

are steroid

diabetes caused by use of steroid

immunosuppressive

agents.

preclinical diabetes, former name for

impaired glucose

tolerance.

puncture diabetes, diabetes produced in an experimental animal by

puncturing the floor of the fourth ventricle in the medulla oblongata;

see Bernard

puncture, under puncture.

renal diabetes, see under

glycosuria.

steroid diabetes, steroidogenic diabetes, glucose intolerance or

overt hyperglycemia induced by glucocorticoids or estrogens; it is due

in part to target tissue insulin resistance and is characterized by a

relatively low incidence of microvascular sequelae.

subclinical diabetes, former name for

impaired glucose

tolerance.

thiazide diabetes, glucose intolerance or overt hyperglycemia

induced by

thiazide diuretics, which inhibit insulin secretion, possibly

through thiazide-induced

hypokalemia.

tropical diabetes mellitus, tropical pancreatic diabetes mellitus,

malnutrition-associated d. mellitus.

Type I diabetes mellitus,

type 1 d.

mellitus.

type 1 diabetes mellitus, one of the two major types of diabetes

mellitus, characterized by abrupt onset of symptoms,

insulinopenia,

and dependence on exogenous

insulin to

sustain life; peak age of onset is 12 years, although onset can be at

any age. It is due to lack of insulin production by the

beta cells of

the pancreas, which may result from viral infection,

autoimmune

reactions, and probably genetic factors;

islet cell

antibodies are usually detectable at diagnosis. When it is inadequately

controlled, lack of insulin causes

hyperglycemia,

protein wasting,

and production of

ketone bodies owing to increased fat metabolism, and the

hyperglycemia

leads to overflow

glycosuria, osmotic

diuresis,

hyperosmolarity,

dehydration,

and diabetic

ketoacidosis. It is accompanied by

angiopathy of

blood vessels, particularly the small ones (microangiopathy),

which affects the retinas, kidneys, and basement membrane of arterioles

throughout the body. Other symptoms include

polyuria,

polydipsia,

polyphagia,

weight loss,

paresthesias, blurred vision, and irritability; if untreated,

diabetic

ketoacidosis progresses to nausea and vomiting, stupor, and

potentially fatal hyperosmolar coma (diabetic

coma). Called also

insulin-dependent,

juvenile,

juvenile-onset,

and Type I d.

mellitus.

Type II diabetes mellitus,

type 2 d.

mellitus.

type 2 diabetes mellitus, one of the two major types of diabetes

mellitus, characterized by peak age of onset between 50 and 60 years,

gradual onset with few symptoms of metabolic disturbance (glycosuria

and its consequences), and no need for exogenous

insulin;

dietary control with or without oral

hypoglycemic

is usually effective.

Obesity and

genetic factors may also be present. Diagnosis is based on laboratory

tests indicating

glucose intolerance. Basal

insulin

secretion is maintained at normal or reduced levels, but insulin release

in response to a

glucose load is delayed or reduced. Defective glucose receptors on

the beta cells

of the pancreas may be involved. It is often accompanied by disease of

various sizes of blood vessels, particularly the large ones, which leads

to premature

atherosclerosis with

myocardial

infarction or

stroke syndrome. Called also

adult-onset,

maturity-onset,

non–insulin-dependent, and

Type II d.

mellitus.

-be´t

-be´t z)

[ Gr. diab

z)

[ Gr. diab

Diabetes

is a disorder characterized by hyperglycemia or elevated blood

glucose (blood sugar). Our bodies function best at a certain

level of sugar in the bloodstream. If the amount of sugar in our

blood runs too high or too low, then we typically feel bad.

Diabetes is the name of the condition where the blood

sugar level consistently runs too high. Diabetes is the

most common endocrine disorder. Sixteen million Americans have

diabetes, yet many are not aware of it. African Americans,

Hispanics and Native Americans have a higher rate of developing

diabetes during their lifetime. Diabetes has potential long term

complications that can affect the kidneys, eyes, heart, blood

vessels and nerves. A number of pages on this web site are

devoted to the prevention and treatment of the complications of

diabetes.

Diabetes

is a disorder characterized by hyperglycemia or elevated blood

glucose (blood sugar). Our bodies function best at a certain

level of sugar in the bloodstream. If the amount of sugar in our

blood runs too high or too low, then we typically feel bad.

Diabetes is the name of the condition where the blood

sugar level consistently runs too high. Diabetes is the

most common endocrine disorder. Sixteen million Americans have

diabetes, yet many are not aware of it. African Americans,

Hispanics and Native Americans have a higher rate of developing

diabetes during their lifetime. Diabetes has potential long term

complications that can affect the kidneys, eyes, heart, blood

vessels and nerves. A number of pages on this web site are

devoted to the prevention and treatment of the complications of

diabetes.  The

human body wants blood glucose (blood sugar) maintained in a

very narrow range. Insulin and glucagon are the hormones which

make this happen. Both insulin and glucagon are secreted from

the pancreas, and thus are referred to as pancreatic endocrine

hormones. The picture on the left shows the intimate

relationship both insulin and glucagon have to each other. Note

that the pancreas serves as the central player in this scheme.

It is the production of insulin and glucagon by the pancreas

which ultimately determines if a patient has diabetes,

hypoglycemia, or some other sugar problem.

The

human body wants blood glucose (blood sugar) maintained in a

very narrow range. Insulin and glucagon are the hormones which

make this happen. Both insulin and glucagon are secreted from

the pancreas, and thus are referred to as pancreatic endocrine

hormones. The picture on the left shows the intimate

relationship both insulin and glucagon have to each other. Note

that the pancreas serves as the central player in this scheme.

It is the production of insulin and glucagon by the pancreas

which ultimately determines if a patient has diabetes,

hypoglycemia, or some other sugar problem.